Looking Glass

Weaving the present of the past with Adrian Jones

How can archives, storytelling and augmented reality (AR) come together to celebrate the histories and futures of Black life in East Liberty, Pittsburgh? We sat down with Adrian to learn more about his project, Looking Glass, creating spaces, the magic of archives, and sparks of repair.

Xiaowei Wang

Could you introduce yourself?

Adrian Jones

This is Adrian Jones reporting live from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Xiaowei

Something that feels important to document is the greater community of Logic School — the cohort and also the people we bring into our community learning space. I'm curious who you brought with you into the Logic School space?

Adrian

I love this question that you posed to us, in our first meeting, about bringing in lineage, bringing in family. Prior to joining Logic School, I actually spent a good amount of time doing some genealogical digging. So I brought with me, my great grandma, Mary Lucille and my great-great-great-great grandfather, Daniel Trueheart. Also, those ancestors and teachers like bell hooks, folks who look like me and folks who live on the margins are with me.

Xiaowei Wang

What was your project, and how did it begin?

Adrian

I really do feel like the space of Logic School, it was a catalyst — the invitation itself lit the fire underneath the pot of all the things that were stewing in me. Some of those things in the pot were the kind of contact that I made with the past, digging through records and learning about my family, things that I read about in local Pittsburgh history, events that shaped the region, the lives and experiences of Black folks in the city. The art and video games I played — those helped shape the project and what it has become.

Looking Glass is a digital archive that folks will be able to access through navigating the neighborhood of East Liberty in Pittsburgh, to discover, remember and commemorate the lives of Black folks and folks who were allied with Black folks, in this neighborhood where Black history and culture has purposely been buried.

Xiaowei

Can you give us some context on East Liberty?

Adrian

The neighborhood, East Liberty, has undergone a lot of shifts. I moved to Pittsburgh in 2017 and folks that I met, seeing me, a young Black man on my journey as a professional in the city, these folks kindly, as we would say, put me on game. There are spaces in the city which have rapidly changed, and East Liberty is one of them. Not coincidentally, neighborhoods where Black people have lived for decades have been targets of disinvestment, gentrification and so-called revitalization. At one point in time, East Liberty was a big commercial center in the city of Pittsburgh. With urban renewal taking place around the 50s, Black families were forced to migrate from the city’s Hill District to other neighborhoods — East Liberty being one of them. Along with that came redlining and white flight, which eventually resulted in East Liberty being mostly comprised of Black folks. Now it looks like Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Developers and city officials have tried to bring it back to what it once was, based on people's imagination of this commercial center. Sadly, from some of the folks that I've spoken to, the way they see it is that poor folks and Black folks are being pushed out of East Liberty, and the story of the neighborhood is being rewritten.

Xiaowei

One of the biggest things that stood out to me was the archives and the archival spark at the beginning of your project. What did you find in the archives?

Adrian

That was a huge spark, it was incredible. The Carnegie Museum of Art has maintained an archive of a photojournalist by the name of Charles "Teenie" Harris. He worked as a photographer for one of the largest Black newspapers at the time, The Pittsburgh Courier. The archive has tens of thousands of his photos, and he took photos of everything and everybody. Those images are just incredible. Being able to have this glimpse of what once was, in all its magnificence, and the beauty of everyday life and people. Seeing those photos helped me understand even more just how incredible the Black folks who made up the fabric of the city were, and are. It's been really special to not only get a glimpse of the beauty of everyday life but to also see the importance of Black folks in this city in shaping culture and events nationally. This includes Teenie Harris and the folks who worked at this newspaper.

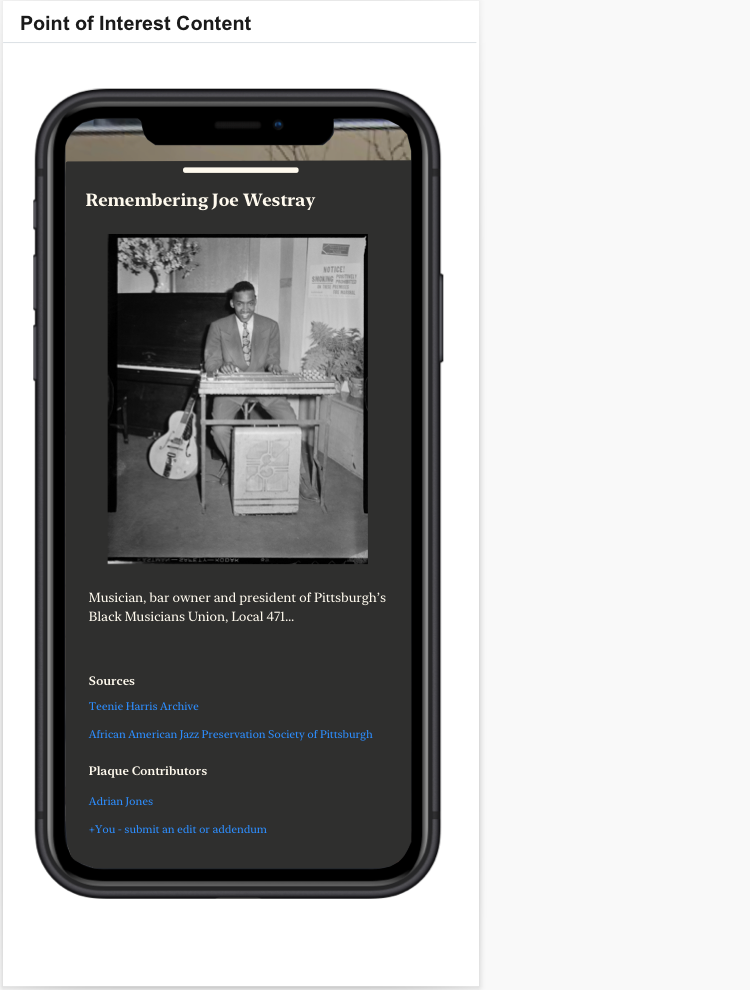

One of the images that I found early on in the archive was captured in East Liberty. It was a photo of Local 471 which was, at the time, a union comprised of Black musicians, mostly jazz musicians. Jazz was critically important to the cultural fabric of the city. I'd seen the image and I was struck by the bit of history that I was able to grab hold of. Learning that there was a musician's union and that these musicians were organized, that their careers were vibrant, and they added to the vibrancy of the city — that was really important to me.

But the story of the union, I slowly learned, was also tied to this forced migration that was caused by urban renewal. At one point in time, the union was in a neighborhood called the Hill District, where urban renewal kicked off and forced residents to scatter throughout the region. So, the union moved to East Liberty. They were in East Liberty for a while. Eventually, around the 60s, because of changing labor laws, the union had to integrate with the white musician's union, Local 60. During the merger, many of Local 471’s records, including membership cards, were “lost”. The Black musicians were already at a disadvantage, being Black and outnumbered by their counterparts, but the convenient loss of records made it even easier to sideline folks. Eventually, most of the former Local 471 members ended up leaving, and their lack of union representation caused them to miss out on gigs and the work they once had. It's tragic.

My experience discovering this history has also been beautiful though. Learning about the agency that these folks had, and the relationships that they had, and again, through the archive, getting these glimpses of how vibrant and beautiful the jazz scene was — it has national significance. Learning that this union was tied to the neighborhood of East Liberty was really special. Through learning about the union, I also ended up discovering Charles Austin. In the 90s, he helped form a group called the African American Jazz Preservation Society of Pittsburgh. They did an oral history of the union, interviewed a whole bunch of its former members, and left behind even more precious archival materials.

Xiaowei

What has that process been like for you, connecting with people about history?

Adrian

I had the opportunity earlier this week to interview someone who grew up in the neighborhood. It's been a really humbling thing to share the project with folks who know what life is like in the neighborhood, who know what it's like to be Black in this city. It's been really humbling to present the project to them and for them to understand its purpose and affirm its value. It's a humbling thing, to be seen as being worthy of upholding these stories, and helping preserve them, and trying to create something that allows these stories and these histories to be accessible to other people. I've spent some time just walking around East Liberty, introducing myself and talking to people. In some sense, these are things that I've done before, but doing them in this context now and doing them with a really clear purpose has been really satisfying. I don't think I'll get over that aspect of it.

Xiaowei

Can you take us through the nuts and bolts of this AR experience?

Adrian

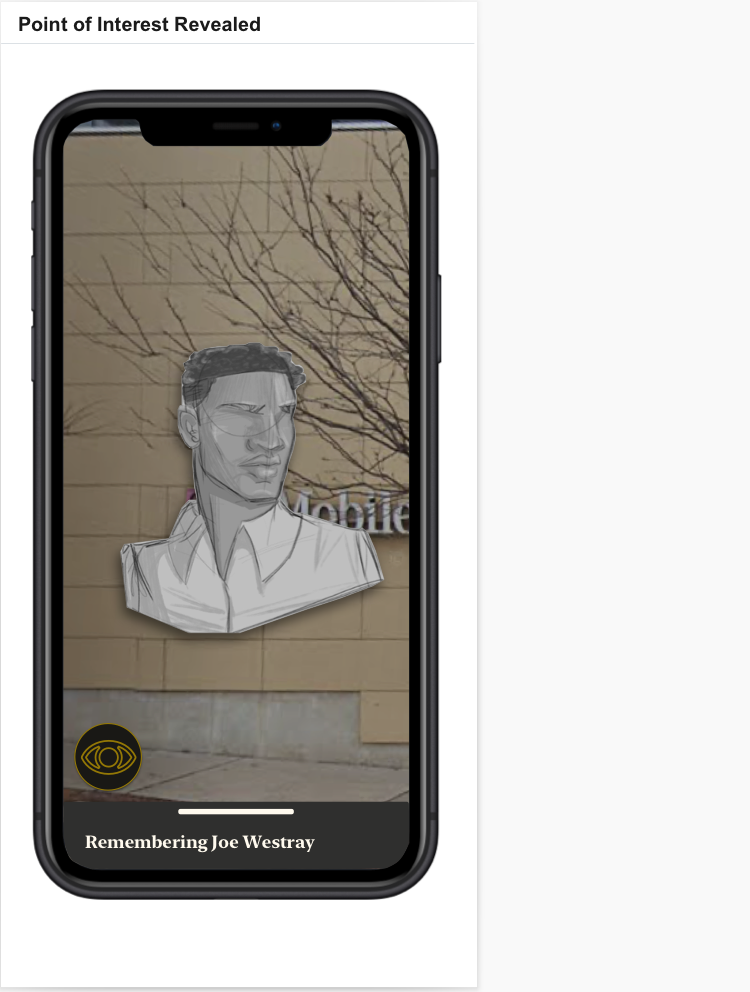

The core functionality I'm envisioning relies on a map of points of interest, the kind you might see if you were to open up Google Maps. Your camera’s feed is always shown alongside this map, so when you arrive at a point of interest, you’re notified that there’s something to be discovered and at the press of a button, you can reveal the digital monument tied to that location. There are people, events, businesses, institutions that should be remembered and discovered — I think it’s important to mark their significance with monuments that can’t be moved. Those augmented reality scenes will be contextualized by written descriptions and, as much as possible, artifacts like images, audio and video. I’m also hoping to make it possible for people to leave behind their own memories and submit photos, videos and audio to tie to a set of coordinates.

Xiaowei

I remember one of our guest lecturers, Ari Melenciano, gave you feedback on thinking about this app as a way of bringing people into the neighborhood as well and ways of supporting Black owned businesses in the neighborhood. I'm curious how you've integrated that feedback into the project.

Adrian

I think the application’s points of interest will be differentiated by type. So there'll be monuments with their own subcategories, there will be memories that people have deposited, and it will also be possible to see institutions and businesses that are still present in the neighborhood. It's also what makes me excited about this kind of medium. I am kind of thinking about it as a means of continuing to affirm the agency that we have to imagine, to re-envision, the environments that we're a part of. We may not be able to physically alter them in the same way that a developer might be able to, but it's possible to use this visual and imaginative space to see it, to paint it as we wish, and to spotlight and place beacons on the places that we care about and want to direct people to.

Xiaowei

What's your wildest dream for this project?

Adrian

Part of this process has just been allowing myself to think about those wild dreams more often and see myself as capable of making those things become reality. That's been one of the dimensions of this work in which I have grown. There are quite a few dreams that I have. If I'm real, a wild dream is for people to be restored to their rightful place in the neighborhood. A wild dream would be for it to be a neighborhood where property and developers don't have more power than the residents. A wild dream would be for people who were forcibly displaced, not just in the city but also in the county, to have proper restitution and proper repayment for the suffering and for the lives that were upended. A wild dream is that this project could play some role in helping those things come about. A wild dream is that, in the same way that I felt emotionally healed and more grounded in myself and in my history, everyone who opens up this application and comes into contact with these artifacts and these stories would experience that same thing.

Xiaowei

Is there anything else you'd like to share with us?

Adrian

Well, I’ll just say this, because we were talking about this last time. Looking Glass was catalyzed by [my participation in] Logic School. I can directly trace it back to the invitation that you and Dorothy made to me and to my peers. There were many office hours where we talked about it and you helped shape the concept and help clarify the direction that I needed to go in. The way that I went about the project early on was critical and it was a direct result of collaborating with you. So I wanted to put that on the record.

Xiaowei

It's a privilege and an honor to bear witness to your whole process, your project, everything that you are dreaming and building. Thank you, Adrian.

Adrian Jones (he/him) is a creative technologist, specializing in web-based software, whose work is shaped by a commitment to all those pushed to the margins.

Looking Glass is a fiscally sponsored project by the Pittsburgh Center for Arts & Media and has recently received grants from Awesome Foundation and the Opportunity Fund. To support the project, visit: https://ajarian.github.io/looking-glass/